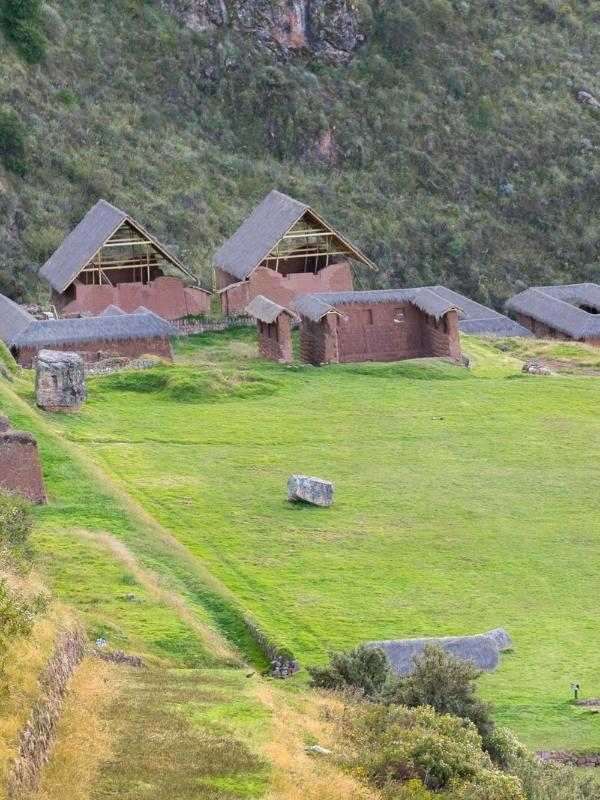

The extensive archaeological complex of Llaktapata is located on the left bank of the Vilcanota, about three kilometers from the Qoriwayrachina bridge. On one side, there is what must have been a shrine, Pulpituyoc, which was the religious center where ceremonies were held in honor of their gods. The Inca site of Llaktapata is one of the largest in the entire network of Inca roads that lead to the citadel of Machu Picchu. It is believed that this site was one of the largest centers of agricultural, textile and pottery production from where the Inca citadel of Machu Picchu was supplied. It was probably inhabited by more than 1,000 inhabitants. On their agricultural terraces the Incas planted different species of corn, potatoes, olluco, chili, squash, beans, fruits such as papaya, soursop, pacay, aguaymanto, achira, sweet potato, yuca, and coca leaves. When the first Spaniards arrived, this site was abandoned and destroyed by order of Manco Inca, to protect the sacred city of the Incas.

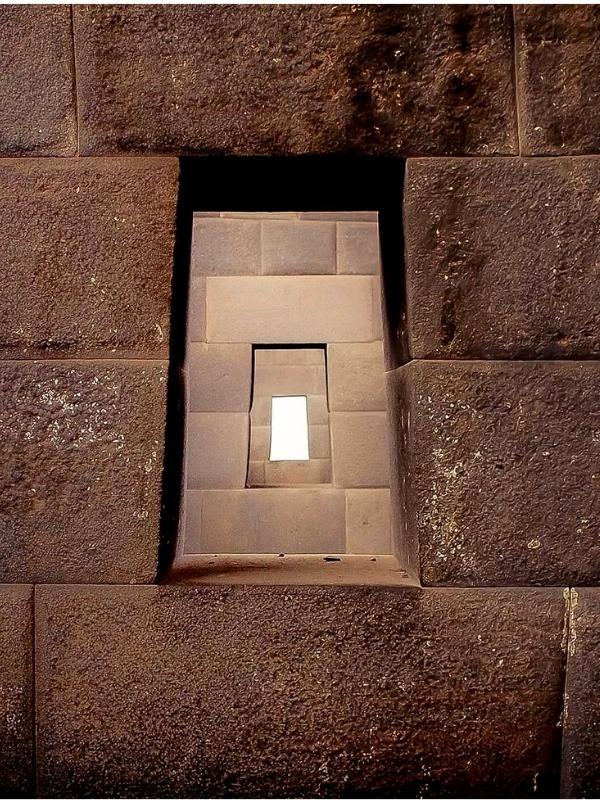

LLaktapata is located on the edge of the left bank of the canyon that forms the Cusichaca. The complex extends over 2,300 meters of altitude and includes groups of enclosures, as well as very extensive terrace works. A view from a distance allows us to appreciate that the two levels of terraces, which are located in the lower sector and limit the complex, take the form of the sinuous edges of a seashell. Perhaps this was also intended to evoke the sea waves, when they are lost on the shores of the coast. In both cases, this recreation must have been intentional and undoubtedly hides a symbolic value, which should not be surprising given the accentuated cult of water in ancient Peru.

In addition, the building included in the Llaktapata complex and known as Pulpituyoc, according to Siles’ observation, also alludes to a snail, following in this what is seen in the form adopted by the so-called Torreón de Machu Picchu, as well as the apse sector of Koricacha in Cusco. The Llaktapata complex, if it had evoked a shell of the family of osteroides, would explain not only the reason for the sinuous contours at its ends, but also the reason for the bulge where the various groups of enclosures are concentrated.

Llaktapata would thus join other examples of iconographic architecture detected by the author, such as Chavín de Huantar, Cerro Blanco in the Nepeña valley, Paramonga. The same is true for the city of Cuzco itself, which was outlined with the body of a feline and the head of a falcon, with its crest taking the form of points that seem to evoke the image of lightning at the same time. The successive rows of platforms sit on a topographical bulge, above the esplanade formed by the upper platform. At the top, the various enclosures are crowded together to form a larger group, which is considered the “urban sector” of Llaktapata and which includes more than a hundred enclosures.

Most of the enclosures were possibly food stores, taking into account that the sites located in the Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu must have served as centers for the production of food intended to promote good harvests. A short distance from Llaktapata, on the left bank of the Cusichaca River, are located architectural complexes such as Tunasmoco, Wilkaraqay and Lioniyoc.