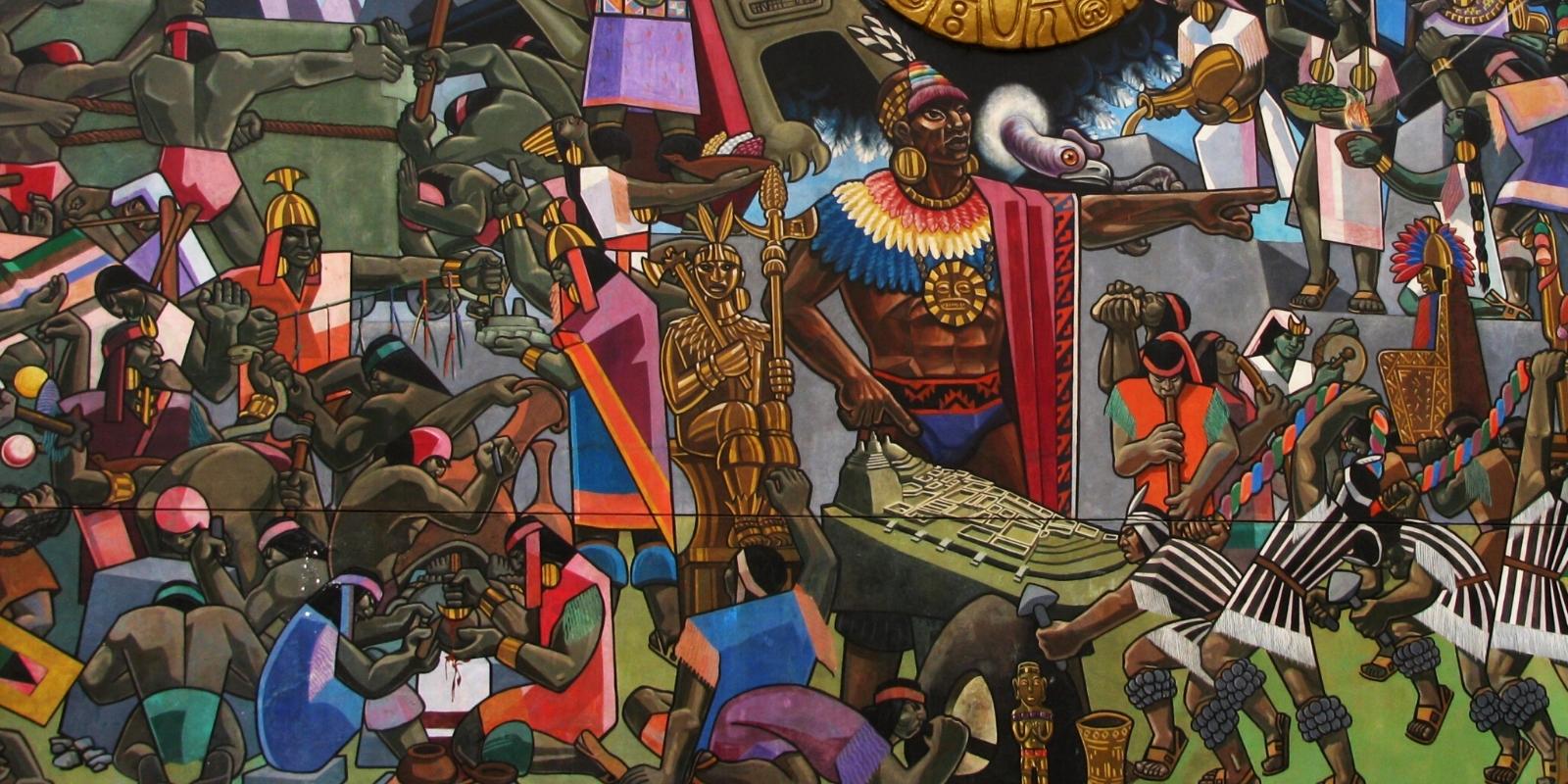

For centuries the men of the Andean societies progressively subdued nature, which means that they knew how to take advantage of accidental discoveries and planned achievements, to enrich the accumulation of knowledge they had about their natural environment, taking advantage of it for their benefit, with which already at the time of Tahuantinsuyo it meant the highest degree of development in scientific, technological and cultural aspects, such as:

• There is a count of thousands of useful, edible, medicinal, poisonous plants, as well as those necessary for construction, elaboration of domestic and ornamental objects.

• Exploitation and classification of animals, fish and insects: edible, dangerous or poisonous; wild, domesticable and working.

• Domain of astronomy, weather phenomena, seasons and their changes for the development of solar and lunar calendars; astrological charts and their application to agricultural cycles, forestry, navigation, etc.

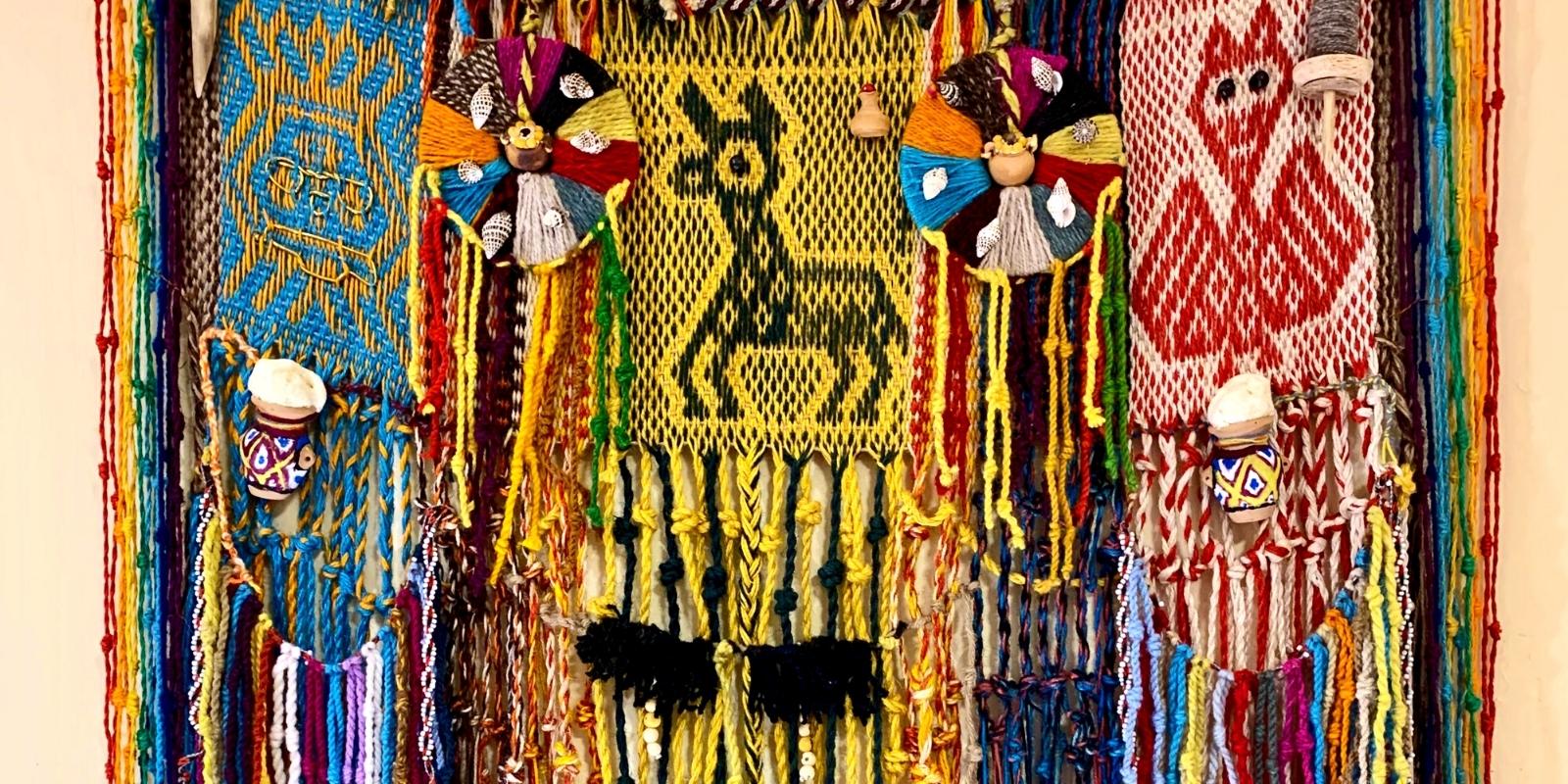

• They generated units of measurement to quantify data, areas, objects, distances, volumes, weights, dimensions, time, etc., and that have evolved into abstract, mathematical and philosophical concepts, as well as equipment for calculating and archiving data. obtained: yupanas and quipus.

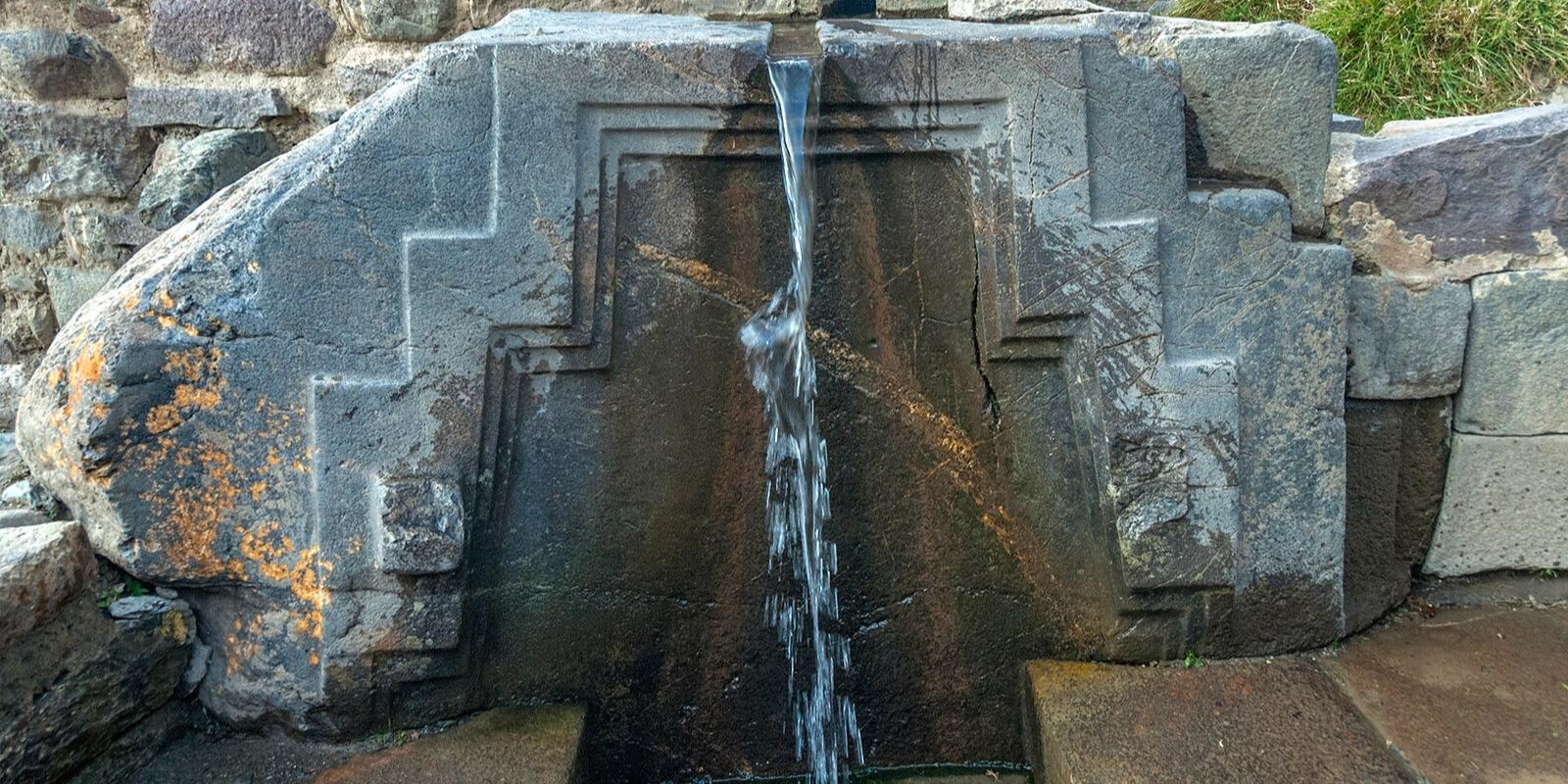

• Manufacture of utensils and instruments to increase the potential of human strength, resulting in increased productivity with less effort and in new relationships with the environment.

Everything said above was used in practical and specialized application: platforms, canals, aqueducts, suspension bridges, great palaces, fortresses and even cities built with the use of carved and polished stone, among others, show the extraordinary capacity, ingenuity and mental and physical strength of the Inca people until the arrival of the Spanish.

The history of the Inca empire is magnified if we consider that, in general, the instruments used in science and technology were natural: stones, metals, vegetable fibers, etc., but their techniques were of complex knowledge for their time, giving as result, great achievements in various decisive fields of scientific, technological and ecological production. This is the first premise to measure the origin and meaning of the material production of the Incas.